“As you ‘walk the Tóchar’, whether on foot or in fantasy, you will be going not only on a spiritual pilgrimage, but on a cultural and historical journey down through the ages also. And both experiences, if fully entered into, should bring about that change of heart and insight of mind which is essential to a pilgrim’s progress.” (p.v) Fr Frank Fahey in Tóchar Phádraig: a Pilgrim’s Progress.

Tóchar Pádraig is a walkway that leads from Ballintubber Abbey to Croagh Patrick. This old pilgrim road stretches c.35 km across mid-Mayo on a route that is both cross-country and on quite rural roads. Annually, Ballintubber Abbey organises four group walks during the summer months. This account is taken from one such event.

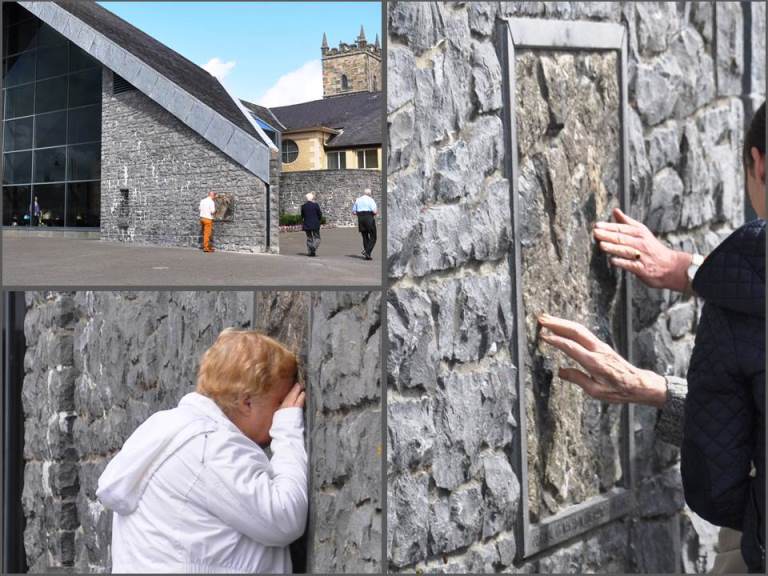

Pilgrims gathering in the morning in Ballintubber Abbey. Mixing and preparing for the pilgrimage ahead.

The gathering in the Abbey is a starting point where Fr Frank Fahey gives an introduction to the route and the concept of pilgrimage. Although some people arrive in the groups – in my case, my father accompanied me – most people don’t know each other. During the day people, through chat and travelling together, will get to know each other better, leading to the emergence of a camaraderie or communitas. My research was a nice topic of conversation which I shared with different people throughout the day.

Pilgrims are invited to light candles before they begin walking. It serves as a means of connect with an intention and the Divine.

A tóchar is an historical route way which served an important land-based transport systems in ancient and medieval times. They were particularly associated with pilgrimages and ecclesiastical foundations. It is speculated that Tóchar Phádraig is based on an earlier route from Cruachain, Roscommon, the seat of the Kings of Connacht to Croagh Patrick, which itself is a site of ancient ritual activity.

The group setting off on the Tóchar, walking across the fields adjacent to the abbey.

The route meanders through the landscape, as we move in meadows, walk along ridges and navigate boggy areas. The removal from the everyday is most definitely expressed in the cross-country sections where soft paths carry us away from the world through quiet patches of nature. Even the on-road sections can be very sedate with little traffic coming by. This withdrawing from the rest of the world and our own lives is a central part of pilgrimage. The landscape itself, is central to the creation of this liminality.

Walking through one of the many fields the Tóchar passes through, the group spreading out as people chat and walk.

The Tóchar follows is known route as much as possible which involves walking on road and through countryside. However, many of the roads are very quiet boreens on which you encounter little, if any, traffic.

Gathering for mass on Boheh stone (St Patrick’s Chair) a former mass rock with ‘cup and ring’ motifs which are a fine example of neolithic rock art.

On the long stretches of road in Teevenacroaghy the group is very spread out. It is in the latter part of the day, as we approach Croagh Patrick.

Only a few climb to the actual summit of Croagh Patrick, as it is an extra undertaking: it is explained to us that the main part of the pilgrimage is the route itself, in doing this you have completed the pilgrimage. This speaks to an ideal of pilgrimage as a journey, rather than a destination. The typical outlook would see the summit of the Reek as a requirement, but in this event our attention is called to other ways of walking and being. It is a readjustment, a pleasant one.

Beginning the climb of the Croagh Patrick ridge form the northern, Teevenacroaghy, side. The path is less clear here, as we walk across rough ground.

As the bus takes our group from Murrisk back to Ballintubber, we chat and rest. We say our goodbyes and each of us, in our previous groupings or as individuals, go on our own paths.

“Reminding yourself that life is a journey not a destination, you now let slow motion time drift past on diaphanous wings while you absorb the timeless sensations and colours of the Mayo countryside.” John O’Dwyer, Pilgrim Trail, The Irish Times, Jul 14, 2012.

Reading:

Tóchar Phádraig: a Pilgrim’s Progress. 1989, Ballintubber Abbey Publication, Mayo.