New Book chapter on Lough Derg

Scriven, R (2018) ‘”I renounce the World, the Flesh and the Devil”: pilgrimage, transformation, and liminality at St Patrick’s Purgatory, Ireland’ in: Bartolini, N, MacKian, S, Pile, S. (eds.) Spaces of Spirituality. Routledge, Oxon: goo.gl/RYzNkg

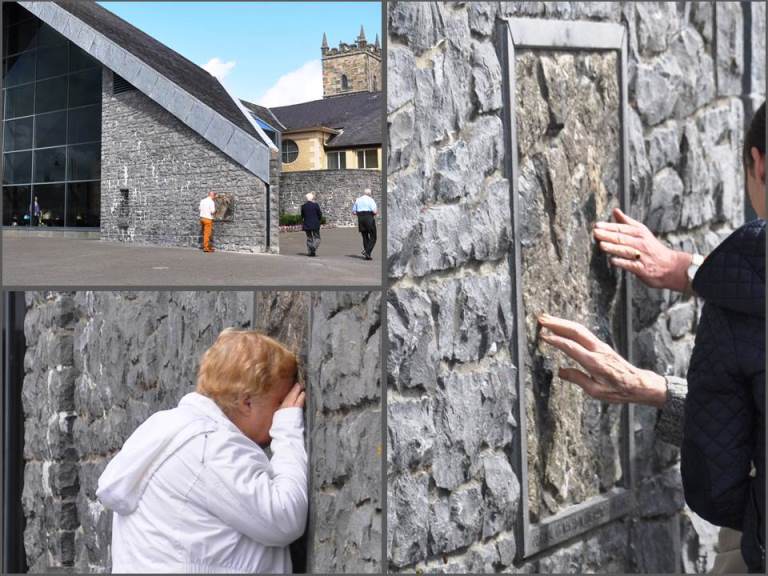

My chapter in the new collection Spaces of Spirituality edited by Nadia Bartolini, Sara MacKian, andd Steve Pile. It explores the transformative potential of pilgrimages, through the example of Lough Derg. By undertaking a spiritual, cultural, or emotional journey that removes one from the everyday, participants enter the liminal state of the pilgrim. This temporary embodied identity facilitates transformative encounters in which participants can express feelings, reflect on their lives, and rejuvenate their faith. The Christian lake-island pilgrimage of St Patrick’s Purgatory – where pilgrims spend three days fasting, praying, going barefoot, and keeping a twenty-four hour vigil – offers a unique setting to explore this ideas in the contemporary world.

Pilgrims kneeling in prayer by St Brigid’s Cross